The desire to go faster, be it on land or water, has been the reason for life and death for some.

Donald Campbell had broken the Water Speed Record (WSR) seven times before such compulsion – the same compulsion that drove Frenchman Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat to the first ever Land Speed Record (LSR) of 39.245mph in 1898 – claimed his life.

At the time of his death, Donald Campbell left behind a legacy of seven successful WSR attempts, the title of being the only man to set the WSR and LSR in the same year, the first to officially break the 400mph barrier, and the record for the fastest LSR by a wheel-driven car.

One reason behind Donald Campbell’s success lay in his genes. His father Sir Malcolm Campbell had set the LSR nine times and the WSR four times during the golden age of record breaking in the 1920s and 1930s before passing away of natural causes in 1948, aged 63.

Unlike his father, Donald Campbell met his maker when his Bluebird K7 boat (Donald Campbell christened all his vehicles ‘Bluebird’ in the same fashion as his father) left the water, flipped and smashed on January 4, 1967, on Coniston Water in the English Lake District.

Unlike his father, Donald Campbell met his maker when his Bluebird K7 boat (Donald Campbell christened all his vehicles ‘Bluebird’ in the same fashion as his father) left the water, flipped and smashed on January 4, 1967, on Coniston Water in the English Lake District.

Three years prior to this incident, in 1964, he set five records in Australia. What more Donald Campbell had to prove to himself, his father, or the public, is difficult to imagine, as four of these records remain upheld to his day.

The WSR still belongs to Campbell, who travelled at 276.3mph across Western Australia’s Dumbleyung Lake. But it’s the LSR he set in July that year on South Australia’s Lake Eyre that captivates legend. It was an effort that, combined with the aforementioned WSR, made him the only man to do both in the same year, and it made Campbell the first to officially break the 400mph barrier and the last to hold the LSR in a wheel-driven car.

Campbell’s efforts leading up to July 1964 had been hard fought. Not only did designing a car fast enough pose a challenge, there was also the logistics of getting it to Lake Eyre and completing a successful run. And there was fear.

Campbell’s efforts leading up to July 1964 had been hard fought. Not only did designing a car fast enough pose a challenge, there was also the logistics of getting it to Lake Eyre and completing a successful run. And there was fear.

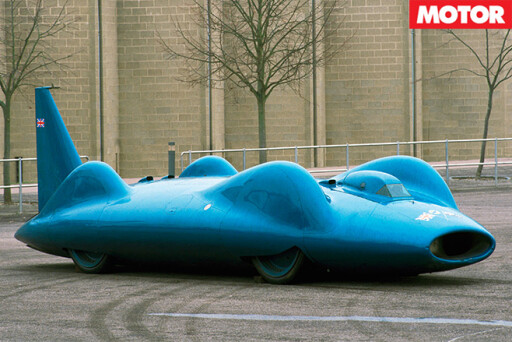

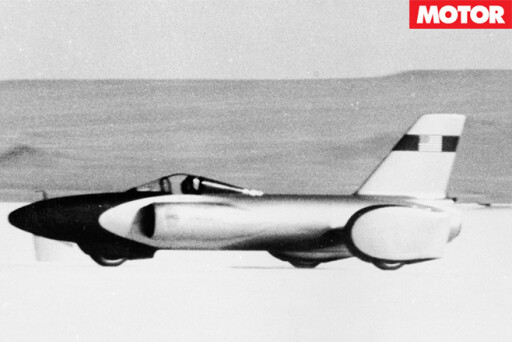

In 1960, on the Bonneville Salt Flats of Utah driving the Proteus Bluebird CN7, Campbell had a horrific crash at around 370mph. He was nearly killed, but as he recovered in his hospital bed he announced he would continue to try and achieve the holy grail of speed records. In effect, Bluebird and its 3016kW Bristol Siddeley gas turbine engine were totally rebuilt and included a massive trapezoidal tail fin to aid stability.

Campbell pencilled in 1962 as the year he would make his assault for the record, but due to unprecedented heavy rains on Lake Eyre everything was postponed 12 months. So in April, 1963, Campbell and his entourage descended on Muloorina, a homestead owned by Elliott Price and his family, which was to act as the base for the project.

Muloorina is some 750km north of Adelaide and an hour’s drive from the nearest town, the railhead at Marree. Lake Eyre is then a further hour’s hard drive over the desert track. There the Australian Army had been enlisted to construct a causeway on to the hard salt lake surface.

Luck was not on Campbell’s side. Problems were enormous and ‘only’ 241mph was achieved before rain again shelved efforts for any serious record breaking. Campbell and his 150-strong crew packed their bags and went home before regrouping in 1964.

Luck was not on Campbell’s side. Problems were enormous and ‘only’ 241mph was achieved before rain again shelved efforts for any serious record breaking. Campbell and his 150-strong crew packed their bags and went home before regrouping in 1964.

From April through to July, 1964, the Bluebird Project again encountered problems.

Campbell’s sponsors were getting flighty and, once again, the weather was against them. Constant rain reduced the salt’s hard surface to a soft slush and Bluebird’s driven wheels kept finding the muddy ooze below it.

Time and money were running out, and the endless delays started to wear down the resilience of everyone involved. Some even concluded Campbell was subconciously afraid to exceed the speed at which he had crashed four years previously.

On one test run with the car approaching 200mph Campbell reported severe vibrations. While some put this down to his imagination, the problem was eventually identified as a build-up of wet salt on the Bluebird’s large wheels causing an imbalance. The attempt of 1964 was looking more and more like the attempt of the previous year.

On one test run with the car approaching 200mph Campbell reported severe vibrations. While some put this down to his imagination, the problem was eventually identified as a build-up of wet salt on the Bluebird’s large wheels causing an imbalance. The attempt of 1964 was looking more and more like the attempt of the previous year.

Campbell began to think the Lake was cursed, in line with the legend of the local indigenous Arabana people. And so interest shown by parties and advocates of the attempt, like Lex Davison and Bib Stillwell, slowly evaporated.

After everyone else had given up, Campbell alone continued to believe the record possible. He would set a new LSR or die trying, even though it seemed the entire attempt would expire like everything else in Lake Eyre’s harsh environs.

Following yet another postponement due to high winds, and with the surface barely holding together, Campbell finally achieved the record: a two-way average of 403.10mph. But after everything Donald Campbell and his team had been through, it seemed almost anti-climactic.

Following yet another postponement due to high winds, and with the surface barely holding together, Campbell finally achieved the record: a two-way average of 403.10mph. But after everything Donald Campbell and his team had been through, it seemed almost anti-climactic.

By the time Campbell broke the world LSR on Lake Eyre the Bluebird was already regarded as a dinosaur. The 1960s were the jet age and the age of space exploration.

His achievements, whilst acknowledged, were never regarded in the same light as those of his father and his contemporaries from the inter-war years, like Henry Segrave, JG Parry-Thomas, Ray Keech, George Eyston and John Cobb. All up it took Donald Campbell nine years – including the near fatal 1960 Bonneville attempt – before his success in Australia in 1964.

American Craig Breedlove had actually gone faster than Campbell in 1963, recording a speed of 407.45mph at Bonneville, but as Spirit of America was a jet-powered three-wheeled motorbike, his record was not recognised by the FIA.

American Craig Breedlove had actually gone faster than Campbell in 1963, recording a speed of 407.45mph at Bonneville, but as Spirit of America was a jet-powered three-wheeled motorbike, his record was not recognised by the FIA.

Campbell’s record was blown away in October, 1964, when the LSR record was broken five times by Americans Tom Green, Breedlove, and Art Arfons in the Green Monster, whose 536.710mph run put Campbell completely in the shade. The record was extended to 600.601mph by Breedlove the following year, before Garry Gabelich achieved 622.407mph in The Blue Flame five years later. This was beaten in 1983 with 633.468mph from Richard Noble’s Thrust 2.

Thrust 2’s ownership of the LSR record remained until September 1997 when Andy Green, an RAF squadron leader, went 714.144mph before he broke the sound barrier (Mach 1.0175) in Thrust SSC supersonic at 763.035mph. Green’s record remains standing but several syndicates around the world are looking to break the 1000mph barrier.

Close to home is Rosco McGlashan who is in the process of constructing Aussie Invader 5R, the most powerful car ever built, which aims to use 62,000lbs of thrust from its bi-propellent liquid oxygen (LOx) and bio-kerosene rocket motor. From the northern hemisphere, combined effort comes from the USA and Canada with the North American Eagle, which has already made 44 test runs.

Close to home is Rosco McGlashan who is in the process of constructing Aussie Invader 5R, the most powerful car ever built, which aims to use 62,000lbs of thrust from its bi-propellent liquid oxygen (LOx) and bio-kerosene rocket motor. From the northern hemisphere, combined effort comes from the USA and Canada with the North American Eagle, which has already made 44 test runs.

But the most promising candidate hails from Britain and the company that has held the LSR for 31 years. Bloodhound SSC is a project chasing something remarkable as it seeks to inspire a new generation with renewed enthusiasm for science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

With Andy Green on board the Bloodhound SSC weighs a whopping 7.5 tonnes and produces 100,669kW in what its makers describe as the ultimate jet- and rocket-powered car. That’s six times the power of a Formula 1 starting grid, so it’s no surprise the Bloodhound uses an F1 Cosworth engine just to power its fuel pump.

The problem now is to find somewhere suitable to run the car, like Utah’s Bonneville or South Australia’s Lake Eyre. There’s a chance of using an alkali surface like the Black Rock Desert where the first supersonic record was set – more pliant than salt and therefore more suitable for a rocket car’s solid wheels. Unfortunately, Black Rock’s lack of rain and overuse has left the surface too rough.

The problem now is to find somewhere suitable to run the car, like Utah’s Bonneville or South Australia’s Lake Eyre. There’s a chance of using an alkali surface like the Black Rock Desert where the first supersonic record was set – more pliant than salt and therefore more suitable for a rocket car’s solid wheels. Unfortunately, Black Rock’s lack of rain and overuse has left the surface too rough.

Wherever the attempt may be, the SSC will certainly leave its mark, and face its own unique and baffling challenges. If successful it will leave its imprint in record books and folklore, in hopes of lasting like the tracks Malcolm Campbell laid on South Africa’s Verneuk Salt Pan in 1929 with his Campbell-Napier Blue Bird. They’re still visible today.

COCKPIT

Campbell’s office consisted of a large steering wheel, flanked by 10 dials, and two pedals, one for the brake, the other for the throttle

ENGINE

The English-built Proteus 705 gas turbine engine produced 3016kW, but was making 3296kW on Bluebird’s record run

AERO

After Campbell’s near-fatal accident on the salt flats of Bonneville, a large tail fin was added to improve stability

BODY

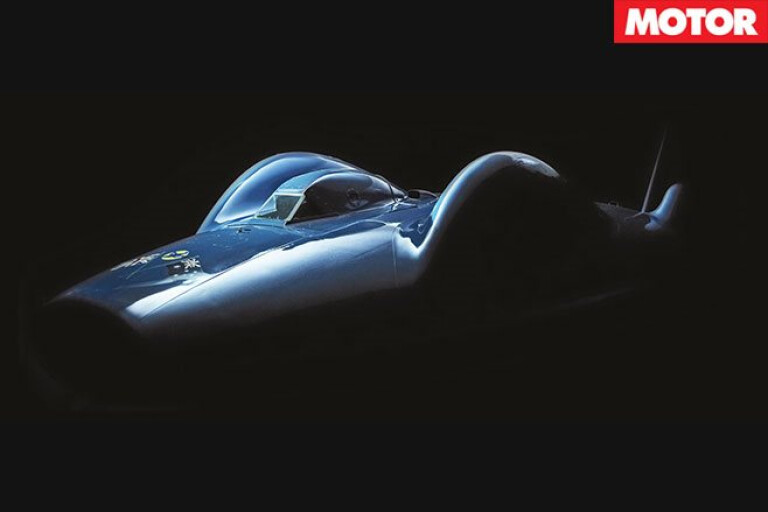

Bluebird’s fuselage was constructed from aluminium. Sheeted, it measured 9m long and 1.5m high

TYRES

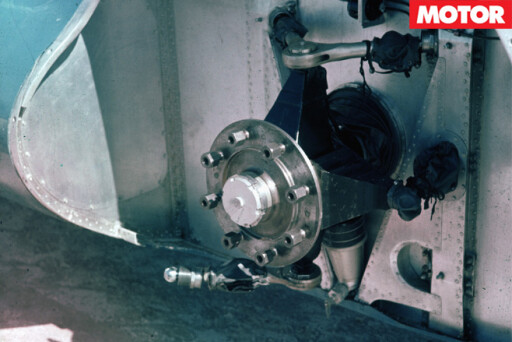

Tyres were inflated with nitrogen to 100psi and mounted on 87kg steel wheels. Made by Dunlop, they were tested to 500mph

BRAKES

In tandem with air flaps that spanned outwards from the rear, four disc brakes able to withstand 1200˚C were used

True Blue

LIKE the tragic Brit he was, when not in the cockpit of land speed record vehicles Donald Campbell drove Jaguars. From 1958 it was a XK150 3.4-litre fixed head coupe, then it was an E-Type from HR Owen in London originally with the registration GLM 37C, the car which he drove until his death at the age of 45 on Lake Coniston in 1967.

LIKE the tragic Brit he was, when not in the cockpit of land speed record vehicles Donald Campbell drove Jaguars. From 1958 it was a XK150 3.4-litre fixed head coupe, then it was an E-Type from HR Owen in London originally with the registration GLM 37C, the car which he drove until his death at the age of 45 on Lake Coniston in 1967.

Both Jags wore the registration ‘DC 7’ and the colour of both cars was, of course, blue. The 150 carries that plate once again today, but of the whereabouts of the E-Type, sold by his widow, singer Tonia Bern, soon after his death, little is now known.

COMMENTS